What is a wine grape variety?

There are thousands of grape varieties used to make wine. Jancis Robinson's huge book Wine Grapes lists over 1200, and these are just the more commercially important ones. We all have an instinctive idea of what a wine grape variety is but it is worth exploring the concept more fully. As you explore wine you will also come across discussion of clones. Just what are clones? And how are they related to varieties?New edition of Emerging Varietal Wines of Australia

This article is an extract from the third edition of the book based on the Vinodiversity website, published in late 2014.

The basic definition of a variety is that all of the individual vines in that variety are derived directly or indirectly from a single seedling. The new plants are propagated from cuttings or grafts from that original mother plant, or from other vines which derive from it. Therefore individual vines of a particular variety are all genetically identical to each other for virtually all of their genes.

Grape seeds, like the seeds of other plants, arise from sexual reproduction. Therefore every variety has two parents, although some seeds arise from self pollination. In the several millennia that grapes have been cultivated untold millions of grape seeds have become seedlings. The vast majority are not cultivated. Seedlings are extremely variable in all sorts of characteristics. Only a tiny minority of seedlings give rise to a variety.

The majority of varieties have arisen by natural crossings where pollen is spread from one plant to another by wind or insects. This cross pollination was more common in the past when vineyards often consisted of several varieties interplanted, rather than the more orderly arrangement today, where vineyards consist of a single variety or several blocks each containing just one variety.

Over the past couple of centuries grape varieties have been deliberately bred. Often the breeding intention is to combine the good characteristics of two varieties into one new variety.

For example the variety Pinotage was deliberately bred in South Africa by crossing Pinot Noir and Cinsaut. The first parent was chosen for its ability to produce fine wines, the second for its ability to thrive in a harsh viticultural environment. In this case the plan was successful, but may thousands of Pinot Noir X Cinsaut seedlings would have been tested and found wanting before the eventual mother Pinotage plant was identified.

Varieties and Clones

All of the plants of a grape variety are derived directly or indirectly via asexual reproduction from a single vine. So their genomes or genetic makeups are very similar, nearly identical in fact, but there are very small differences. Sometimes these differences can become very important. To find out how these differences occur we need to look at how a grape vine (or any other plant) grows.

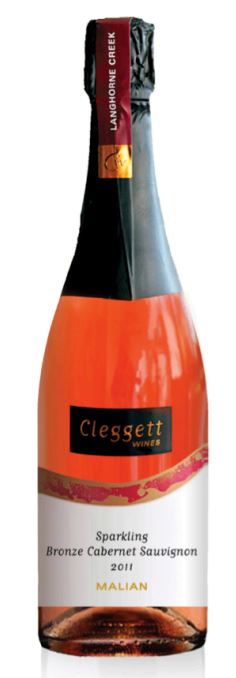

For example in a vineyard in Langhorne Creek a Cabernet Sauvignon plant started producing bunches of bronze rather than dark berries on one cane. A mutation had occurred so that all of the cells in that particular arm of the vine carried a different gene involved in the colouring of the grapes. When cuttings were taken to propagate new vines they all produced bronze berries and the new clone was called Malian.

Later a further mutation produced a white clone called Shalastin. Cleggett Wines now make and market wines from these new clones. From the consumer's point of view they are distinct varieties, but strictly speaking they are clones of the same variety - Cabernet Sauvignon.

More often the mutations causing new clones to arise are more subtle than the change of berry colour. The new clone may be more vigorous in the vineyard, it may have disease resistance, or there may be slightly different compounds in the skin giving rise to better (or worse) aroma and flavours in the wine it produces.

Older varieties and those that have been grown in a wide variety of viticultural environments tend to have many more recognised clones, and the clones are more diverse in their characteristics.

Why do grape varieties matter?

Careful selection of the appropriate wine grape variety is critical for successful grape growing and wine making. Different can have vastly different characteristics in the vineyard and in the wine produced.Consumers need to know at least something about varieties to chose wines they like. But there is much more to it than that. This topic is explored more fully in this article.

Keep in touch with Vinodiversity

Just enter your details below and you will receive an occasional newsletter letting you know all about the alternative varietal wine scene in Australia and beyond.

Now available for delivery in Australia, and internationally

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.